The Haxe language has been on my radar for years. Over the summer, I came up with a great trial project to do in Haxe, which would help me learn both the language and its ecosystem. In this article, I’ll summarize my recent experiences with Haxe: the great parts, the meh parts, and everything in between.

- The Project

- Getting the Old Toolchain Running

- Why Haxe?

- Discovering the Haxe World

- Modernizing

- Distribution

- Thoughts

The Project

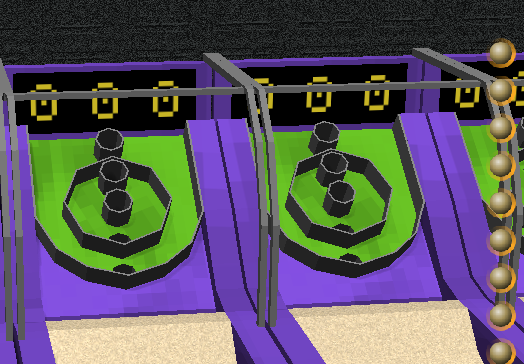

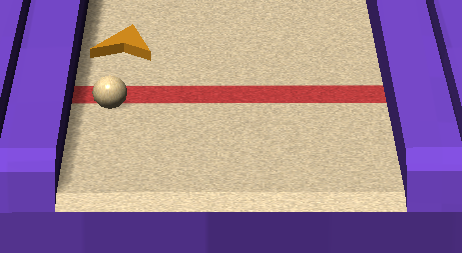

The trial project idea was to remake a 3d Flash skeeball game which I’d written for my mom back in 2013 (but never published). When Flash died, the game became unplayable for her. I could have looked into using an emulator like Ruffle to restore functionality, but

- that’d have been less of a win-win than me also learning Haxe, and

- my mom had asked for a few features over the years and I certainly wasn’t about to get the old Actionscript/Flash toolchain up and running again.

Or so I thought...

Getting the Old Toolchain Running

When I sat down to outline what would need to be done for the rewrite, I realized that I actually didn’t remember the original game very well. I had the source and assets (in a zip file, not a git repo), so I could have figured a lot of it out by just looking that over, but if it were possible, it’d be better to actually see the original for reference.

Technology Ages Quickly

In order to compile and run the original code, I ended up tracking down:

- a copy of Windows XP

- a few old versions of .NET

- an old version of Java

- the FlashDevelop IDE

- Adobe Flash Player

- the Adobe Flex SDK

The Adobe stuff was pretty difficult to find, since most old links point to Adobe’s site, and Adobe has taken everything Flash-related down and redirected those links. Hence the copy of Windows XP: if the shady sites I’d resorted to (in order to get the Adobe stuff) had fouled up the goods, the potential damage incurred was going to happen inside VirtualBox.

Version Numbers

Once I had FlashDevelop running inside VirtualBox, the next challenge was getting the old code to compile. There were only four dependencies, but 2013 me hadn’t left anything as nice as a Maven POM file. There was only a FlashDevelop project config file, which provided a few hints at dependency version numbers. Luckily, all four dependencies still existed on Github, and with some trial and error, I was able to compile and run the old skeeball game, albeit without 3d acceleration.

Why Haxe?

That brings us to Haxe. There are lots of 3d game frameworks and engines out there to choose from, so why did I initially go with the Haxe language and ecosystem?

- Haxe’s syntax was originally very similar to Actionscript’s and so I figured I might be able to save some time there by using parts of the old code. (This assumption turned out to be false, for various non-syntax-related reasons.)

- The 3d engine I used originally, Away3d, had been adapted for Haxe. Again, I thought there might be time savings here. (Again, I was wrong. Though Away3d exists in the Haxe world, it is far from the best 3d engine in the Haxe world.)

- Haxe makes lots of promises about cross-compilation on its website. The idea of remaking the skeeball game once and then having the source available in many flavors hooked me.

Discovering the Haxe World

So then, let’s talk about the Haxe world a bit.

Haxe was created in 2005 by Nicolas Cannasse, who still maintains it. It’s gone through four major versions in that time. The most recent version was released in October.

Haxe the Language

I know and have extensively used Java, Javascript, Python, and SQL. I like Python. I love Java. I’m lukewarm about Javascript and SQL. That should give you some context when I say that Haxe the language is delightfully modern.

It has:

- strong typing with type inference

- functional programming support

- first class functions, lambdas

- map/filter/reduce

- static extensions

- properties

- switch expressions

- algebraic data types

- macros

- generics

It’s worth going into a bit more detail about a few of these.

Flexible Ergonomics

Haxe’s type system offers strong guarantees with flexible ergonomics.

I prefer to include explicit types everywhere and use private/final by default…

private function createMesh(radius:Float, px:Float, py:Float, pz:Float):Mesh {

final primitive:Sphere = new Sphere(radius);

final mesh:Mesh = new Mesh(primitive);

mesh.setPosition(px, py, pz);

return mesh;

}

… but that’s not everyone’s cup of tea. The below version of the above function is still valid Haxe, and types are still checked the same way at compile time.

function createMesh(radius, px, py, pz) {

var primitive = new Sphere(radius);

var mesh = new Mesh(primitive);

mesh.setPosition(px, py, pz);

return mesh;

}

Macros

Haxe’s macro system is powerful enough to completely denecessitate tools like Gradle functions and Lombok. There are multiple kinds of macros available. Though I could go on about their usefulness for pages here, instead I’ll just link to this article, which does precisely that.

Minor Criticisms

Despite all the modern language features in Haxe 4, some parts of the standard library are a bit lacking. For example, there is no standard library implementation of a set, and the string utils are limited.

These things do exist in Haxelib, Haxe’s package manager, but even there, they’re not always usable, depending on your choice of language version and game framework.

Haxe’s Ecosystem

That brings us to Haxe’s ecosystem, which is, in my opinion, its greatest weakness.

The Good

Let me start off by saying that it’s remarkable that a language with such a small community behind it has the tooling and resources it does at all.

Developer Experience

There are a handful of VSCode plugins which together make for an actual decent coding experience. Most impressive is that the language server (yes, Haxe has one) understands your custom build macros and offers autocompletion and error checking which take said macros into account. The VSCode plugins don’t always work perfectly; sometimes you have to manually restart the language server (or just VSCode) to make incorrect error highlighting go away, but that’s still nicer than some languages which don’t even have such tools.

Dependency Management

Haxelib has a lot of packages available and works at least as well as Python’s pip, or other similar package managers. More importantly though, Haxelib has an option available to use a git repo as a package directly. This helps a lot when the latest git repo release is much newer than the latest Haxelib release.

The Bad

I offer these criticisms constructively. Overall, my experience was a positive one.

Fragmentation

There are a lot of game frameworks in various states of maintenance/disarray for such a small language. It’s not easy to figure out which one is best, except perhaps by looking at the number and quality of games made with each, and the recency of updates on Github. Even Haxelib has a competitor now, an alternative package manager called Lix.

Broken Promises

Haxe the language keeps its ambitious cross compilation promises, but Haxe the ecosystem does not. It’s common for Haxelib libraries to only support a subset of Haxe’s compile targets.

The Ugly

There is exactly one viable 3d engine in the Haxe ecosystem: Heaps.io. Created by Shiro Games (Northgard, Dead Cells), it is a well designed and capable engine, which you should only use if you absolutely must.

Heaps Documentation

Shiro’s documentation is lacking at best and completely wrong in places at worst. It is simply accepted in the Heaps community that Shiro can’t be bothered with that sort of maintenance.

Heaps Community

Given the abysmal state of the Heaps documentation, how should an outsider approach a new Heaps project? Just figure it out somehow.

I did figure it out, by reading through the Heaps source and experimenting. I did not ask many questions in the Heaps Discord channel, mostly because of the way I saw others’ beginner questions repeatedly addressed: with rude and condescending remarks. I would like to make a point of it that this unwelcoming and abrasive behavior is unique to the Heaps sub-community (and even there limited to certain individuals, but also widely tolerated). For the most part, the Haxe community is warm and inviting.

Also, let me be clear here: no one in the Heaps Discord channel was rude to me, but the consistently hostile responses to other newcomers in that channel were shocking enough that I felt compelled to mention them here.

Hashlink

Heaps supports two compile targets: web and Hashlink. Hashlink is a virtual machine (like the JVM) created by none other than Haxe’s Nicolas Cannasse. Hashlink’s fun party trick: transpiling Haxe to very portable C code. (You can also distribute Hashlink bytecode and the Hashlink virtual machine, and Shiro does this.)

HL/C

I didn’t want to go the bytecode + VM distribution route because

- I would learn more if I compiled C code, and

- C code would be more performant and that might make a difference in my physics-engined-based game.

Using Microsoft’s instructions, I compiled a C hello world. A few guides later, I had a compiling Hashlink project. Basic pipeline, check.

Physics

The visuals were settled then: the skeeball game remake was going to be in C-compiled Hashlink Haxe with Heaps. Next up then, was getting a physics engine working.

Oimo

While there are various 2d physics engines in Haxelib, there is only one 3d physics engine, OimoPhysics. Just kidding! There’s also HaxeBullet, but I didn’t find that until I was in deep with Oimo. Oops!

Thinking that OimoPhysics was my only option, I tried integrating it into my POC project. It didn’t compile. Turns out, Oimo hasn’t seen an update in a while and was only ever partially updated for Haxe 4. So, I forked it, patched it myself, pointed Haxelib to my git repo, and continued.

The Roadblock

Then I discovered that Oimo doesn’t support concave collisions. If you give it a concave shape, it will simply discard all inner vertices. In other words, if you give Oimo a star, Oimo treats it like a pentagon. If you give Oimo a bowl, Oimo treats it like you’ve filled the bowl with cement.

This was a major problem for a skeeball game: I needed the ball to roll up a concave lane and into one of five concave holes.

Had I known about HaxeBullet, I could have just switched to it, since it does support concave collisions, but I didn’t.

The Workaround

After a few quick tests, I set out to carve up my 3d skeeball lane asset into many convex pieces. Though Oimo treats a a star as a pentagon, it treats five overlapping diamonds in the shape of a star as a star.

This part was pretty tedious. I had to relearn Blender, which I hadn’t touched since I made the original version of the game. (This time, I took notes with Obsidian.)

All said and done, I ended up with 101 convex shapes. I wrote a custom parser, loaded my data into Oimo, and it worked: the ball could fall into the holes.

Modernizing

At my last job, I had a running joke that despite whatever the git history said, any code with my name on it and older than two years was actually written by some other David Conway.

If you’re always learning and always improving, your old code is always going to look awful to you. Such was the case with the code for the original version of the skeeball game. It was all in one giant source file. Thankfully it was broken up into functions, but all within one class, so all class-scoped variables were effectively globals.

Having recently finished Game Programming Patterns by Robert Nystrom, I was eager to modernize the design. The new version has factories, dependency injection, and data oriented ECS-like systems. (I did “ECS-like” systems instead of proper ECS because with few exceptions, there is one of everything which appears onscreen.)

Additionally, I made a few other upgrades.

- I made good use of Heaps’s resource management macros.

- I kept the mutable game state isolated from everything else.

Distribution

The last bit to figure out was distribution, and the questions there mostly centered around packaging and licensing.

Packaging

Heaps has a standard option to package up all game resources inside a .pak file which you distribute alongside your executable. These .pak files are useful for modding/patching, so I went with that option instead of a resources directory.

Licensing

Compiling for Windows meant that I’d need to distribute, among other DLLs, mscvr120.dll. I didn’t know if I’d need any kind of licensing or permissions from Microsoft to do that. The answer turns out to be, Microsoft allows you to distribute that DLL freely.

Thoughts

Conclusions are hard, but here goes.

I love Haxe the language. It’s pleasantly modern, and its tools are great. I only experienced one part of the Haxe ecosystem (Heaps), possibly the best and the worst in different ways.

Ultimately, I was able to power through all the annoying stuff and accomplish what I set out to do, which at least means that as a whole, the Haxe world is good enough. I look forward to exploring other languages and frameworks, but maybe I’ll return some day.