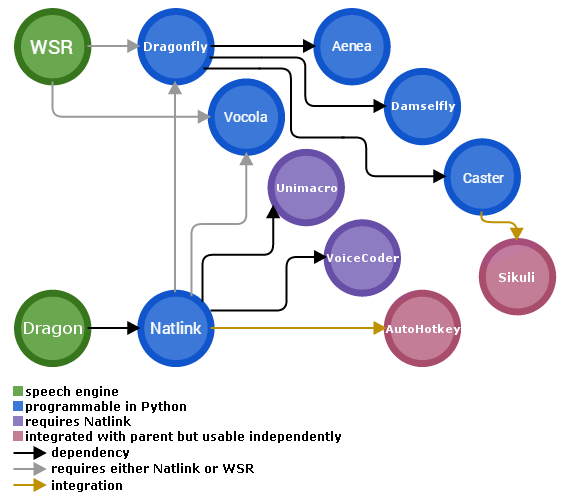

Last time, I talked about why Dragon NaturallySpeaking (version 12.5) is currently the best choice of speech engine for voice programming, and how Natlink ties Dragon to Python. Natlink is a great tool by itself, but it also enables lots of other great voice software packages, some of which are explicitly geared toward voice programming, and all of which also offer accessibility and productivity features. In this article, I’m going to go over the purposes and capabilities of a number of these, their dependencies, and how to get started with them.

I’m also going to rate each piece of software with a star rating out of five. ( ★ ) The rating indicates the software’s voice programming potential (“VPP”), not the overall quality of the software.

The Natlink Family

Unimacro, Vocola*, and VoiceCoder all require Natlink and are developed in close proximity with it, so I’ll start with them.

Unimacro (documentation/ download) [VPP: ★★☆☆☆]

Unimacro is an extension for Natlink which mainly focuses on global accessibility and productivity tasks, like navigating the desktop and web browser. It’s very configurable, requires minimal Python familiarity, and as of release 4.1mike, it has built-in support for triggering AutoHotkey scripts by voice.

Unimacro is geared toward accessibility, not voice programming. Still, it’s useful in a general sense and has potential if you’re an AutoHotkey master.

Vocola (documentation | download) [VPP: ★★★★★]

Vocola is something of a sister project to Unimacro; their developers work together to keep them compatible. Like Unimacro, Vocola extends Dragon’s command set. Unlike Unimacro, which is modified through the use of .ini files, Vocola allows users to write their own commands. Vocola commands have their own syntax and look like the following.

Select Two Words = {Ctrl+Shift+Right_2};

Sort by (Date=e | Sender=n | Subject=s) = {Alt+v}o $1;

scroll down 1..10 = {down_ Eval($1*20) };

When you start Dragon, Vocola .vcl files are converted to Python and loaded into Natlink. Vocola can also use “extensions”, Python modules full of functions which can be called from Vocola. These extensions are where Vocola’s real power lies. They allow you to map any piece of Python code to any spoken command.

Vocola’s syntax is easy to learn, it’s well-documented, and it gives you full access to Python, so it’s a powerful step up from Natlink. However, it’s not quite as easy to call Python with as Dragonfly is and its community became somewhat displaced when the SpeechComputing.com forum site went down. (Though it has regrouped some at the Knowbrainer.com forums.)

VoiceCoder (download) [VPP: ★★★☆☆]

Also sometimes called VoiceCode (and in no way related to voicecode.io), VoiceCoder’s complex history is best documented by Christine Masuoka’s academic paper. VoiceCoder aims to make speaking code as fluid as possible, and its design is very impressive. (Demo video – audio starts late.)

For having been around for so long, it still has a fairly active community. Mark Lillibridge recently created this FAQ on programming by voice with the help of said community.

VoiceCoder does what it does extremely well, but that’s pretty much limited to coding in C/C++ or Python in Emacs. Furthermore, since its website and wiki are down, documentation is sparse.

Dragonfly (documentation | download | setup) [VPP: ★★★★★]

In 2008, Christo Butcher created Dragonfly, a Python framework for speech recognition. In 2014, he moved it to Github, which has accelerated its development. The real strength of Dragonfly is its modernization of the voice command programming process. Dragonfly makes it easy for anyone with nominal Python experience to get started on adding voice commands to DNS or WSR. Install it, copy some of the examples into the /MacroSystem/ folder, and you’re ready to go. Here’s an example.

from dragonfly import (BringApp, Key, Function, Grammar, Playback,

Dictation, MappingRule, Text)

def my_function():

print "put some Python logic here"

class MainRule(MappingRule):

mapping = {

"lock Dragon": Playback([(["go", "to", "sleep"], 0.0)]),

"open explorer": BringApp("explorer"),

"remax": Key("a-space/10,r/10,a-space/10,x"),

"[use] function": Function(my_function),

"else": Text("else"),

}

grammar = Grammar('sample')

grammar.add_rule(MainRule())

grammar.load()

It’s pure Python and unlike vanilla Natlink, it’s API is very clean and simple. It’s well documented and it has a growing community on Github. Furthermore, the _multiedit.py module enables fine-grained control of CCR. (CCR is “continues command recognition”, the ability to string spoken commands together and have them executed one after the other, rather than pausing in between commands. Vocola and VoiceCoder can also use CCR, but not with as much flexibility.)

The Dragonfly Family

Due to Dragonfly’s ease of use, a large number of Dragonfly grammar repositories have appeared on Github recently, as well as some larger projects.

Aenea (Github) [VPP: ★★★★☆]

Aenea is software which allows you to use Dragonfly grammars on Linux or Mac via virtual machine (or own any remote computer for that matter). Getting it set up is pretty complicated but worth it if your workspace of choice (or necessity) is not a Windows machine. Aenea is basically a fully realized version of what Tavis Rudd demonstrated at Pycon.

Damselfly (Github) [VPP: ★★★☆☆]

Damselfly lets you use Dragonfly on an installation of Dragon NaturallySpeaking on Wine on Linux, cutting Windows out of the picture entirely.

Caster (download | Github/ documentation) [VPP: ★★★★☆]

Like VoiceCoder, Caster aims to be a general purpose programming tool. Unlike VoiceCoder, Caster aims to work in any programming environment, not just Emacs. It improves upon _multiedit.py by letting you selectively enable/disable CCR subsections. (“Enable Java”, “Disable XML”, etc.) It allows you to run Sikuli scripts by voice. And, like VoiceCoder, it uses Veldicott-style fuzzy string matching to allow dictation of strange/unspeakable symbol names. It is still in active development and contributions or suggestions are welcome.

Some Final Thoughts on Open Source Voice Programming

The open source voice programming community has come along way since its days of obscure academic papers and mailing lists. Community spaces have developed and produced fruit. The projects listed above are downright awesome, all of them, and I’m sure more are coming. There is still much to be achieved, much low hanging fruit to be plucked even. All this has happened in fifteen years. I’m looking forward to the next fifteen.

* To be more precise, Vocola 2 requires Natlink. There are several versions, and the most recent version does not.